In the previous post, we discussed the foundations for automatic data encryption of properties during serialisation using System.Text.Json. In this post, we’ll continue our journey, moving toward removing our fake “encryption” and replacing it with actual encryption. Along the way we’ll establish some abstractions and a design that allows us to develop flexible encryption and decryption code. Originally, I expected this series to be just two parts, but it has become clear that I need to break things down a bit further as I expected my example.

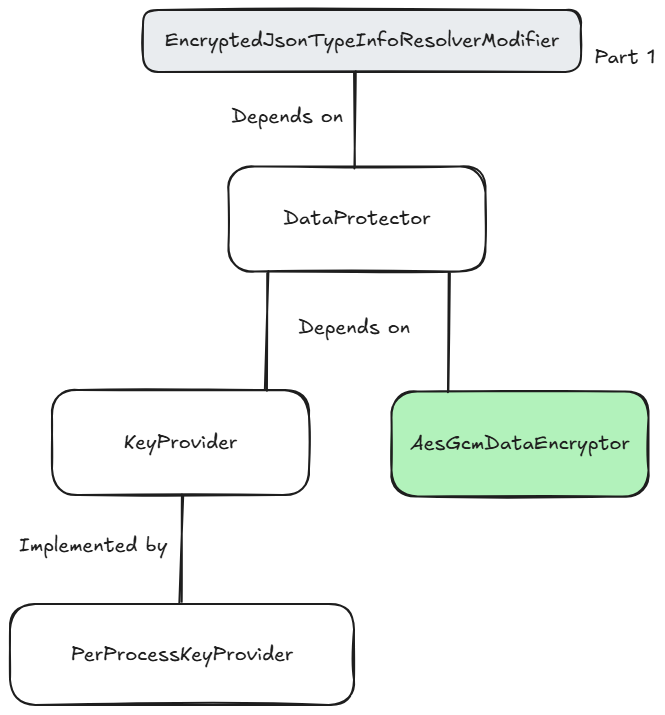

Here is the planned architecture that we’ll get to in the next few posts. We’ll also create other implementations (not shown) of KeyStore once this design is achieved. In part 1, we completed the first version of the

EncryptedJsonTypeInfoResolverModifier.

Today, we’re going to build out the

AesGcmDataEncryptor (in green), which can encrypt data using the AES-GCM standard. It’ll mostly be a wrapper around the built-in .NET cryptography API.I want to warn you, once again, that while this is reasonably fully featured, it is not production-ready code and is still demoware. I haven’t thoroughly tested it, so it’s by no means battle-hardened. Use with caution!

Let’s start with the basic shape of this class.

using System.Buffers;

using System.Diagnostics.CodeAnalysis;

using System.Security.Cryptography;

using System.Text;

namespace JsonEncryptionBlogExample;

public sealed class AesGcmDataEncryptor

{

public const int NonceSize = 12; // 96-bit

public const int TagSize = 16; // 128-bit

public const int Aes128KeySize = 16; // 128-bit

public const int Aes256KeySize = 32; // 256-bit

public bool TryEncrypt(ReadOnlySpan<char> plainText, ReadOnlySpan<byte> aesKey,

Span<byte> cipherTextDestination, out int bytesWritten)

{

// TODO

}

public bool TryDecrypt(ReadOnlySpan<byte> cipherTextBytes, ReadOnlySpan<byte> aesKey,

[NotNullWhen(true)] out string? plainText)

{

// TODO

}

public static (int PlainTextLength, int CipherTextLength) CalculateByteLengths(ReadOnlySpan<char> plainText)

{

if (plainText.Length == 0)

return (0, 0);

var plainTextByteLength = Encoding.UTF8.GetByteCount(plainText);

return (plainTextByteLength, NonceSize + plainTextByteLength + TagSize);

}

private static bool IsValidKeySize(int keySize) =>

keySize == Aes128KeySize || keySize == Aes256KeySize;

}

First, we define some constants for the lengths of the encryption inputs. The nonce and tag are core concepts in AES-GCM to provide a combination of security and integrity for the encryption process. We’re using the recommended sizes here. Our code will also support both 128-bit and 256-bit keys, which will be provided by the consumer of the code.

There are two scaffolded methods that we’ll complete shortly that provide the encryption and decryption functionality.

TryEncrypt accepts a ReadOnlySpan<char>, which includes directly passing in a string instance, containing the plain text. It then requires a ReadOnlySpan<byte> containing the key to be used for encryption. We’ll later implement a concept of a KeyStore, which will provide these keys. The method is designed for low allocation use, so it also requires a Span<byte> as the destination for the ciphertext that will be produced. Its out parameter returns the number of bytes written.TryDecrypt has a very similar signature, but in reverse. The first parameter is ReadOnlyString<byte> representing the ciphertext bytes to be decrypted. The next ReadOnlySpan<byte> parameter is the AES key, and the out value is the plain text string.There are three static helper methods involved in calculating the byte lengths required for plain text and ciphertext. When using AES GCM, our final bytes include more than just our encrypted data. We also store the nonce and tag value in the final payload; therefore, we account for those additional bytes. Because we’re designing low-allocation code and using

Span<T> for most of our data, we need to calculate the sizes upfront in order to rent appropriately sized arrays.Next, we’ll implement the

TryEncrypt method.

public bool TryEncrypt(ReadOnlySpan<char> plainText, ReadOnlySpan<byte> aesKey,

Span<byte> cipherTextDestination, out int bytesWritten)

{

bytesWritten = 0;

if (plainText.Length == 0)

return true;

if (!IsValidKeySize(aesKey.Length))

return false;

var (plainTextByteLength, cipherTextByteLength) = CalculateByteLengths(plainText);

if (cipherTextDestination.Length < cipherTextByteLength)

return false;

var rentedPlainTextArray = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(plainTextByteLength);

try

{

var plainTextBytes = rentedPlainTextArray.AsSpan();

if (!Encoding.UTF8.TryGetBytes(plainText, plainTextBytes, out var plainTextBytesWritten))

return false;

using var aesGcm = new AesGcm(aesKey, TagSize);

Span<byte> nonceAndTagBuffer = stackalloc byte[NonceSize + TagSize];

var nonceSpan = nonceAndTagBuffer[..NonceSize];

var tagSpan = nonceAndTagBuffer[NonceSize..];

RandomNumberGenerator.Fill(nonceSpan);

aesGcm.Encrypt(nonceSpan, plainTextBytes[..plainTextBytesWritten],

cipherTextDestination.Slice(NonceSize, plainTextBytesWritten), tagSpan);

nonceSpan.CopyTo(cipherTextDestination);

tagSpan.CopyTo(cipherTextDestination.Slice(NonceSize + plainTextBytesWritten, TagSize));

bytesWritten = NonceSize + plainTextBytesWritten + TagSize;

return true;

}

finally

{

ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Return(rentedPlainTextArray, clearArray: true);

}

}

Upfront, there is some validation being done. If the input plain text bytes are 0, we have nothing to do. If the provided key length is not valid for 128-bit or 256-bit encryption, we return false. Next, we calculate the required size in bytes of both the plain text (characters at this stage) and the final ciphertext. If the destination

Span<byte> we have been provided for the final ciphertext (including the nonce and tags) is too small, we also return false because we can’t encrypt into an undersized buffer.With the validation complete, the first job is to encode the plain text characters into UTF8 bytes. The code first rents a suitably sized byte array and then creates a

Span<byte> over the memory. We can then use the TryGetBytes method on UTF8 to encode the plain text characters from the original string value into the byte array.We can now initialise an

AesGcm instance with our key and our required tag size. The computed tag will later be used for integrity validation. When we later encrypt our data, we’ll need to pass in a ReadOnlySpan<byte> containing the nonce value and a Span<byte> large enough for the computed tag value. This non-sensitive data is only a few bytes, so the code stack allocates the appropriate number of bytes. This is a very efficient way to handle small, temporary memory, and it’s made safe through explicitly typing the result as Span<byte>.We slice the stack-allocated memory to get our nonce span and our tag span. For the nonce, we need to provide a unique value per encryption operation. In this code, we use the

RandomNumberGenerator to fill it. For this use case and example, this is sufficient. There is, over time, a very small chance of generating the same nonce, which can render AES-GCM insecure. You’d need to perform billions of encryptions before that risk becomes a real concern. A richer implementation could use an incrementing value to avoid the risk of repeating the same nonce with the same key, but it’s likely overkill for this scenario. We could also rotate keys periodically to avoid the risk of the same key and nonce being used.We now have all the pieces in place and can call Encrypt on our

AesGcm instance. We pass the span of bytes containing our nonce value, the plain text bytes, the destination Span<byte> slices to the correct size and the span of bytes for the tag to be written into. Note that with AES-GCM, we know the number of bytes required for the ciphertext will match the number of bytes being encrypted. The slice operation slices the destination starting from the index matching the nonce size, as we will later write the nonce bytes into the destination span, since it is also required for decryption. In fact, the next line of code copies the nonce bytes into the start of the destination span.The tag span will also have been populated with the value used to verify the integrity of the encrypted data, so we also copy this to the end of the destination span.

We then set the bytesWritten out variable with the actual bytes written to the cipherTextDestination span and return true. Inside the finally block, the rented array used for the plain text bytes is returned to the pool. Crucially, we specifically pass true for the second argument so that it is cleared first. We don’t want future renters having access to the plain text data.

We must also implement the

TryDecrypt method:

public bool TryDecrypt(ReadOnlySpan<byte> cipherTextBytes, ReadOnlySpan<byte> aesKey,

[NotNullWhen(true)] out string? plainText)

{

plainText = null;

if (cipherTextBytes.Length < NonceSize + TagSize || !IsValidKeySize(aesKey.Length))

return false;

var plainTextLength = cipherTextBytes.Length - NonceSize - TagSize;

var plainTextLength = cipherTextBytes.Length - NonceSize - TagSize;

var rentedPlainTextArray = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(plainTextLength);

var plainTextBytes = rentedPlainTextArray.AsSpan(0, plainTextLength);

try

{

var nonce = cipherTextBytes[..NonceSize];

var encryptedPayload = cipherTextBytes.Slice(NonceSize, plainTextLength);

var tag = cipherTextBytes.Slice(NonceSize + plainTextLength, TagSize);

using var aesGcm = new AesGcm(aesKey, TagSize);

aesGcm.Decrypt(nonce, encryptedPayload, tag, plainTextBytes);

plainText = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(plainTextBytes);

return true;

}

catch

{

return false;

}

}

Again, there is some validation up front to check that the ciphertext bytes are at least long enough to hold the nonce and tag and that the provided key is a valid length.

We can then calculate the plain text byte length by subtracting the nonce size and tag size and rent an appropriately sized array, before creating a span over the bytes we will populate.

We extract the spans for the nonce, payload and tag by slicing the incoming cipherTextBytes. We can initialise a new

AesGcm instance with the key and the tag size before calling Decrypt, passing the nonce span, the encrypted payload, tag and the Span<byte> for the plain text to be decrypted into.We ultimately require a string for the decrypted data, so we can use

UTF8.GetString, passing in the plain text bytes from our decryption operation. When everything goes to plan, we return true from this method; otherwise, any exceptions will cause us to return false.And that’s it! The encryption process is quite simple. It’s the use of low-allocation spans that makes it a little more complex, but even so, you now hopefully understand what’s happening at this layer. I’ve used low-allocation code here because I know this will be on hot paths for my authentication flow, and I want to avoid heavy overhead for each request in the application where I will eventually use this code.

As this part ended up being quite long, we’ll leave it there, and in the next part, we can focus on the

KeyProvider abstraction.Other posts in this series:

- Part One

- Part Two – This post!

Have you enjoyed this post and found it useful? If so, please consider supporting me: