In this post, I introduce a simple new language feature of C# 8 called using declarations. Based on the odd tweet or two that I have seen pass through my Twitter feed, this feature is like Marmite (sorry, UK reference there). You either love it or you hate it. The opinions seem to be quite polarised. There’s a definite split of those who favour the feature vs those who do not. I’m on the love side of the fence!

Using Statements

Before we dive into the new syntax, let’s quickly review its predecessor, the using statement. Using statements are a convenient way to write code which ensures that an IDisposable object is correctly disposed of. It’s entirely possible to achieve this today without using statements, by manually calling the Dispose method on such objects after you are finished using them.

Using statements let us conveniently wrap the use of an IDisposable object, such that it will be automatically disposed of after use.

For example, take this simple piece of code:

This code introduces a type called TestDisposable which’ implements’ the IDisposable interface.

The Main method creates an instance of this type and calls the DoSomething method. The using statement is applied to ensure that after we’re done with the instance, it is correctly disposed. Notice that the use of the instance is inside a nested block of code.

Let’s see how that same code looks after compilation. To explore the resulting code, I’ve built the sample in release mode, then used a tool called JustDecompile to inspect the DLL and decompile the source.

Focusing on just the Main method, the decompiled code helps show what the using statement has been expanded to. An instance is first created on line 3. Within a try block, its DoSomething method is called. A finally block is included which disposes of the instance. The use of the finally block ensures that the object is disposed of, even if the DoSomething method caused an exception to be thrown.

EDIT: 22-01-2020 – The exact behaviour of try/finally is a little more complex than I firsted describe above. Finally will run when the code in the try block returns and generally that will be true when an exception is thrown. Unhandled exceptions which can crash the application may not allow the finally code to execute before crashing. Thanks to “chucker23n” on Reddit for raising a discussion about this. It’s worth also reading the try/finally documentation which states:

“If the exception is not caught, execution of the

finallyblock depends on whether the operating system chooses to trigger an exception unwind operation.”

Pretty straight-forward code. You could certainly write it yourself if you needed to. However, it’s more verbose, and it would be possible to forget the disposal entirely or introduce a bug. In more complex code, where you use multiple IDisposable types, there would be a code explosion of try/finally blocks.

Using Declarations

Let’s now replace the Main method with a version that applies the new C# 8 syntax.

The main thing I hope you notice is the lack of nesting in this refactored code. With the using declaration syntax, you do not introduce an extra block of nested code. Instead, you declare the instance as you would any other, preceding it with the using keyword.

Personally, I prefer this style, especially if I have more than one IDisposable type to deal with.

“When is the object disposed of though?”, I hear some of you wondering.

When applying the using declaration syntax, the object is disposed of when you leave the scope of the code in which it was declared. In this simple case, that’s when we exit this method.

Let’s look at the resulting decompiled code for this refactored method.

This code is the same as the decompiled code in the earlier example. The object is used within a try block and disposed of from within a finally block. Nice!

Understanding the Scope

There’s not much else to show in regards to using declarations. It’s a small change to the syntax you use when writing your code. Before we conclude, let’s ensure that we understand how the scope affects the disposal of the object.

Here’s some slightly more complicated code:

This code snippet introduces a loop. I’ve used a while loop here, but it could just as easily be a for or foreach loop too. Other than the loop, the code is the same as before.

The question though is, when is the object disposed of? Is it at the end of the method as we saw before?

Here’s the decompiled code.

Hopefully, this is what you were expecting. Since the object was declared inside the while loop, the scope of the loop is used for the disposal of it. Each time the code loops, a new instance is created, used and disposed of. The disposal code is identical to the examples we’ve looked at before. The only change here is the scope.

What if we move the declaration outside of the while loop?

Taking a look at the decompiled code again…

Now we can see that the testDisposable instance is scoped to the method, the enclosing block, and is available for re-use within the while loop. The while loop itself moves inside the try block.

A Real-World Example

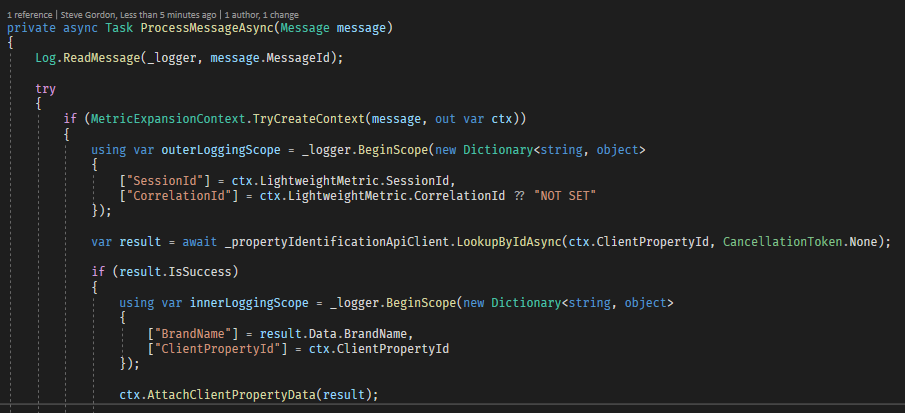

So far, we’ve looked at some straightforward sample code. Let me quickly show a screenshot of some real-world code where the use declaration has been useful. I’ve chosen to include a screenshot here because it’s more useful to show the code in its real environment.

This code comes from a message processing Worker Service. After receiving the message, it’s first validated and wrapped in a context object which maintains some state about the processing that is about to take place.

I’m using two logging scopes (_logger.BeginScope) here to enrich my log messages with some extra fields which make my log data more useful. Logging scopes remain in effect for all logs that are emitted within the scope. The scope can be ended by disposing of it.

This code makes use of using declarations to ensure the correct disposal occurs. Before C# 8, this code required two extra layers of nesting, which I found harder to read when scanning through the code.

Summary

As with many things in software development, there are many ways to tackle the same objective. As I mentioned; nothing is stopping you from manually disposing of all IDisposable instances in your code. Doing so requires proper use of the try/finally block to ensure that the disposal takes place, regardless of exceptions.

The using statement syntax is a common-place way to achieve the same goal, with less code. This makes it easier to read and maintain the code. The compiler is responsible for maintaining proper disposal code.

In my opinion, the using declaration syntax takes this one step further to reduce one more layer of nesting and the lines of code needed to dispose of instances correctly. I find this a little easier to read, and the scoping behaviour is pretty clear. Just look at the level of nesting (the block of code) that your using declaration is declared within. That’s the scope of its lifetime.

Have you enjoyed this post and found it useful? If so, please consider supporting me: