I’ve recently begun making use of a relatively new (well, it’s a little over a year old at the time of writing) feature called “Channels”. The current version number is 4.5.0 (with a 4.6.0 preview also available as pre-release) which makes it sound like it’s been around for a lot longer, but in fact, 4.5.0 was the first stable release of this package!

In this post, I want to provide a short introduction to this feature, which I will hopefully build upon in later posts with some real-world scenarios explaining how and where I have successfully applied it.

WARNING: The sample in this post is very simplified to support learning the concepts. In a real-world application, you will want to study the various consumer and producer patterns properly. While it is slightly out of date in terms of the naming, this document provides some good examples of the producer/consumer patterns you may consider.

What is a Channel?

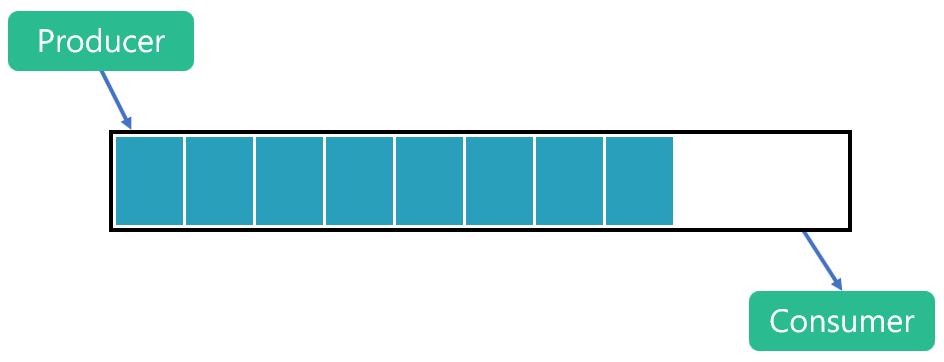

A channel is a synchronisation concept which supports passing data between producers and consumers, typically concurrently. One or many producers can write data into the channel, which are then read by one or many consumers.

Logically a channel is effectively an efficient, thread-safe queue.

Why use System.Threading.Channels?

Before we look at working with channels, it’s worth spending a moment to introduce a concrete scenario. My primary use of channels so far has been within a queue processing worker service.

I have one producer task continually polling a queue for messages, which are written to the channel as soon as they have been received. Concurrently, I have a consumer task which performs the processing steps for each message. It reads from the channel, processing each message in turn. A benefit of this approach is that my producer/consumer functionality has now been separated and data can be passed via the channel. My producer can be fetching more messages from the queue at the same time as my consumer is processing the previous batch. While my producer and consumer keep pace with one another, there is a small efficiency gain with this technique. If either outpaces the other, I can either create more producer or consumer tasks to achieve higher throughput or with bounded channels, take advantage of back pressure to balance the flow.

I’ll describe the message processing flow in more detail in a future post. For this post, we’ll focus first on the basics.

Getting Started with System.Threading.Channels

To begin using channels we need access to the library.

System.Threading.Channels is available as a NuGet package which can be referenced in your application in order to begin using the channels feature. It is not part of the BCL (base class library) in .NET Framework or .NET Core (prior to version 3.0). Since preview 7 of .NET Core 3.0, this library is included with .NET Core. System.Threading.Channels can be used by .NET implementations supporting .NET Standard 1.3 and higher.

For this post, I’m going to concentrate on a very simplified console application scenario. This application won’t do anything useful but will allow us to work with a concurrent producer(s) and consumer(s), exchanging data via a channel. A full sample, which includes three scenarios, can be found in my ChannelSample GitHub repo.

Creating a Channel

To create a channel, we can use the static Channel class which exposes factory methods to create the two main types of channel.

CreateUnbounded<T> creates a channel with an unlimited capacity. This can be quite dangerous if your producer outpaces you the consumer. In that scenario, without a capacity limit, the channel will keep accepting new items. When the consumer is not keeping up, the number of queued items will keep increasing. Each item being held in the channel requires some memory which can’t be released until the object has been consumed. Therefore, it’s possible to run out of available memory in this scenario.

CreateBounded<T> creates a channel with a finite capacity. In this scenario, it’s possible to develop a producer/consumer pattern which accommodates this limit. For example, you can have your producer await (non-blocking) capacity within the channel before it completes its write operation. This is a form of backpressure, which, when used, can slow your producer down, or even stop it, until the consumer has read some items and created capacity.

We won’t cover these producer/consumer patterns in this post, so I’m going to use a single unbounded channel in my sample. For real-world applications, I recommend sticking to bounded channels.

var channel = Channel.CreateUnbounded<string>();

Using the preceding line of code, I’ve created an unbounded channel which will hold string objects. Since this is a generic factory method, we can create channels for any type of object we need to use.

The channel has two properties. Reader returns a ChannelReader<T> and the writer, a ChannelWriter<T>.

Writing to a Channel

We can write via the ChannelWriter in a variety of ways which suit different scenarios. As this is purely an introduction, I’ll use the WriteAsync method.

await channel.Writer.WriteAsync("New message");

This line of code will write a string into the channel. Since the channel we’re using for this post is unbounded, I could also use the following line of code which will try to write synchronously. It will return false if the write fails, which should not happen for an unbounded channel.

bool result = channel.Writer.TryWrite("New message");

Reading from a Channel

Reading from a channel also presents a few choices which each suit different consumer patterns. The one I’ve employed most often in my applications so far, avoids the need to handle exceptions and will loop, awaiting an object being available on the channel to consume.

This code uses a while loop to keep a constant consumer running. In the final sample, you will see that the producer(s) and consumer(s) start concurrently.

The call to reader.WaitToReadAsync is awaited. Only when a message is available, or the channel is closed will it awaken the continuation. Once an object has been written, this method will return true, and we can attempt to consume it. Note that there is no guarantee, due to potential of multiple consumers, that an item will still be available by the time we execute the loop body.

That’s why I use TryRead here which now attempts a synchronous read from the channel. In many cases, we expect this to succeed since we’ve only just continued as a result of WaitToReadAsync completing. For some channels, with infrequently written items and many consumers, it’s possible another consumer may get to the item first.

It’s also important to realise that channels manages the synchronisation here to avoid multiple consumers receiving the same item. The channel maintains the order of items added to the channel, so your consumers receive them as they were written. With many consumers, you will need to synchronise between them if the order is important.

If the channel has been closed, because the producer has signalled that no new items will be added, once all items have been consumed, WaitToReadAsync will return false when it completes. At this point, we exit the while loop as consumption can also end.

Bear in mind that this pattern may or may not suit your planned consumer scenario.

Sample Scenarios

The sample application, which you can clone from GitHub, has a basic implementation of three scenarios. You’re welcome to read through the code to get an understanding of how channels can be applied.

I’ve created methods which create a producer and consumer so that in scenarios where I need more than one, I can easily create them. They both accept an identifier so that when logging, we can see which instance is which. They also accept a delay so that we can simulate different workloads.

The producer adds a simple string message to the channel and logs the creation of the message to the console. The consumer simply reads a message awaits reading a message from the channel and writes its value to the console.

Single Producer / Single Consumer

In this example, a single producer and a single consumer are created. The producer has a slightly longer delay than the consumer so we would expect a single consumer to meet the demand. Both the consumer and producer tasks are started concurrently.

We register a continuation on the producer task so that it triggers completion of the consumer once it completes.

If you choose to run this sample, you should see each message being produced and immediately consumed.

Multi Producer / Single Consumer

This sample demonstrates a multi producer, single consumer scenario. Two producers are created, both with a simulate workload delay of 2 seconds. A single consumer is created with a 250ms simulated processing delay. Since consumption is much quicker than the production of messages, by starting multiple instances of the producer we can balancer things better.

This can be a good pattern when you have very simple processing needs, but the retrieval of messages is comparatively slower. You can make better utilisation of your resources by ensuring you produce roughly an equivalent number of messages as your single consumer can handle. In this case, we have headroom to start more than just two producers.

Single Producer / Multi Consumer

This sample demonstrates a quite common scenario where producing messages (such as reading from a queue or message bus) is fairly rapid, but the processing workload is slower and more intensive. In such a case, we can find a balance such that we have a single producer, and we scale the number of consumers to allow us to keep pace.

In this sample, the producer is able to produce a message every 100ms, but our consumers take 1.5 seconds to handle each message. Having scaled out to 3 instances of the consumer, we increase the processing throughput as we can process three messages in parallel.

If you run this sample, you will see that we still don’t keep pace entirely with the producer, and since this channel is unbounded, over time, we will build up an ever-increasing backlog.

Summary

The Channels feature hasn’t had a tremendous amount of press, so it’s not something you’re likely to find in everyday use at the moment. However, it is a powerful tool for simplifying many producer/consumer patterns in .NET. Any time you need to exchange items between Tasks you will find channels is a pretty convenient and straightforward way to get started. In future posts, we’ll explore more options for real-world use of channels. I hope this post inspires you to take them for a spin. I’d love to hear in the comments below about the scenarios you apply them to.

Have you enjoyed this post and found it useful? If so, please consider supporting me: